Note: A version of this article first appeared as a guest blog post written for Cloudera, linked to a webinar presentation on May 4, 2022. See the sign-up link in the comments. This version has minor changes to fit the tone & audience of this newsletter, and tie in with previous themes. This version is also published on my LinkedIn newsletter with a comments thread (here).

Telcos and other CSPs are rethinking their approach to enterprise services in the era of advanced wireless connectivity - including their 5G, fibre and Software-Defined Wide Area Network (SD-WAN) portfolios.

Many consumer-centric operators are developing propositions for “verticals”, often combining on-site or campus mobile networks with edge computing, plus deeper solutions for specific industries or horizontal applications. Part of this involves helping enterprises deal with their data and overall cloud connectivity as well as local networks. (The original MNO vision of delivering enterprise networks as "5G network slices" partitioned from their national infrastructure has taken a back seat. There is more interest currently in the creation of dedicated on-premise private 5G networks, via telcos' enterprise or integrator units).

At the same time, telecom operators are also becoming more data- and cloud-centric themselves. They are using disaggregated systems such as Open RAN and cloud-native 5G cores, plus distributed compute and data, for their own requirements. This is aimed at running their networks more efficiently, and dealing with customers and operations more flexibly. There are both public and private cloud approaches to this, with hyperscalers like Amazon and disruptors such as Rakuten Symphony and Totogi promising revolutions in future.

As I've said for some time, “The first industry that 5G will transform is the telecom industry itself.”

This poses both opportunities and challenges. Telcos’ internal data and cloud needs may not mirror their corporate customers’ strategies and timing perfectly, especially given the diverse connectivity landscape.

If operators truly want to blend their own transformation journey with that of their customers, what is needed is a much broader view of the “networked cloud” and "distributed data", not just the “telco cloud” or "telco edge" that many like to discuss.

Networked data and cloud are not just “edge computing”

Telecom operators’ discussions around edge/cloud have gone in two separate directions in recent years:

- External edge computing: The desire by MNOs to deploy in-network edge nodes for end-user applications such as V2X, IoT control, smart city functions, low-latency cloud gaming, or enterprise private networks. Often called “MEC” (mobile edge computing), this spans both in-house edge solutions and a variety of collaborations with hyperscalers such as Azure, Google Cloud Platform, and Amazon Web Services.

- Internal: The use of cloud platforms for telcos’ own infrastructure and systems, especially for cloud-native cores, flexible billing, and operational support systems (BSS/OSS), plus new open and virtualised RAN technology for disaggregated 4G/5G deployments. Some functions need to be deployed at the edge of the network (such as 5G DUs and UPF cores), while others can be more centralised.

Of these two trends, the latter has seen more real-world utilisation. It is linked to solving clear and immediate problems for the CSPs themselves.

Many operators are working with public and private clouds for their operational needs—running networks, managing subscriber data and experience, and enabling more automation and control. While there are raging debates about “openness” vs. outsourcing to hyperscalers, the underlying story—cloudification of telcos’ networks and IT estates—is consistent and accelerating. The timing constraints of radio signal processing in Open RAN, and the desire to manage ultra-low latency 5G “slices” in future 3GPP releases are examples that need edge compute. There may also be roles for edge billing/charging, and various security functions.

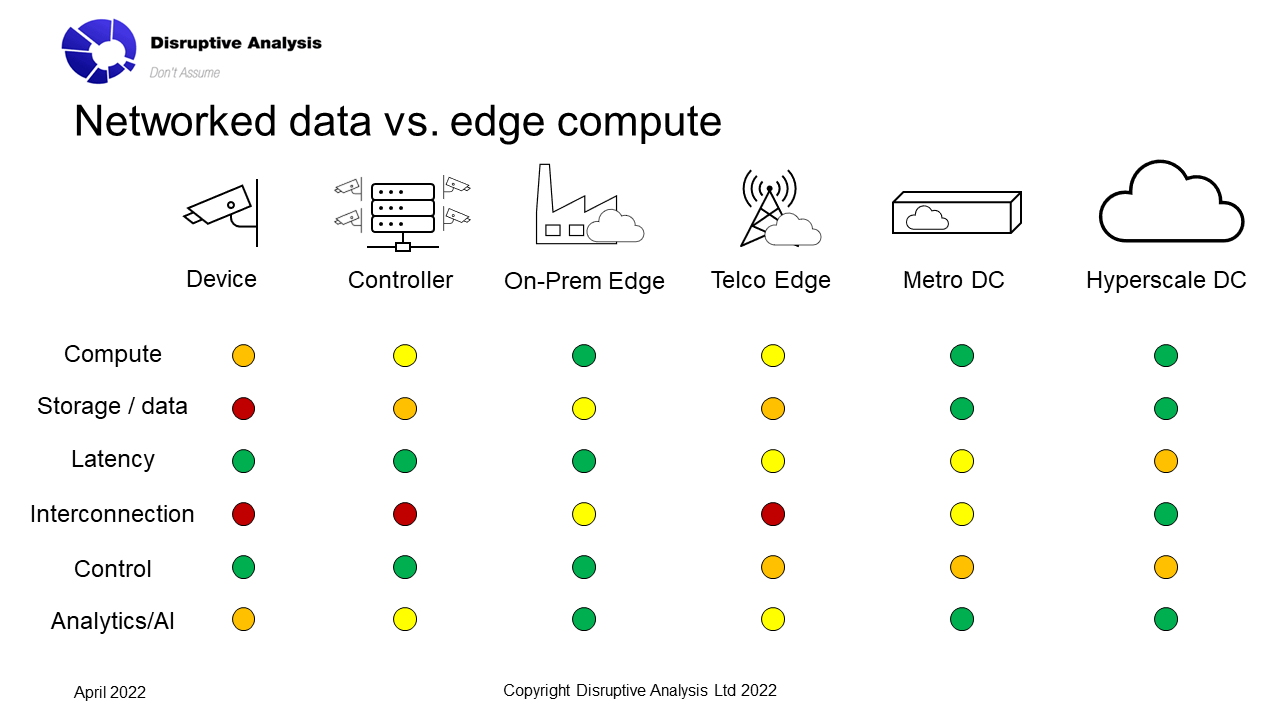

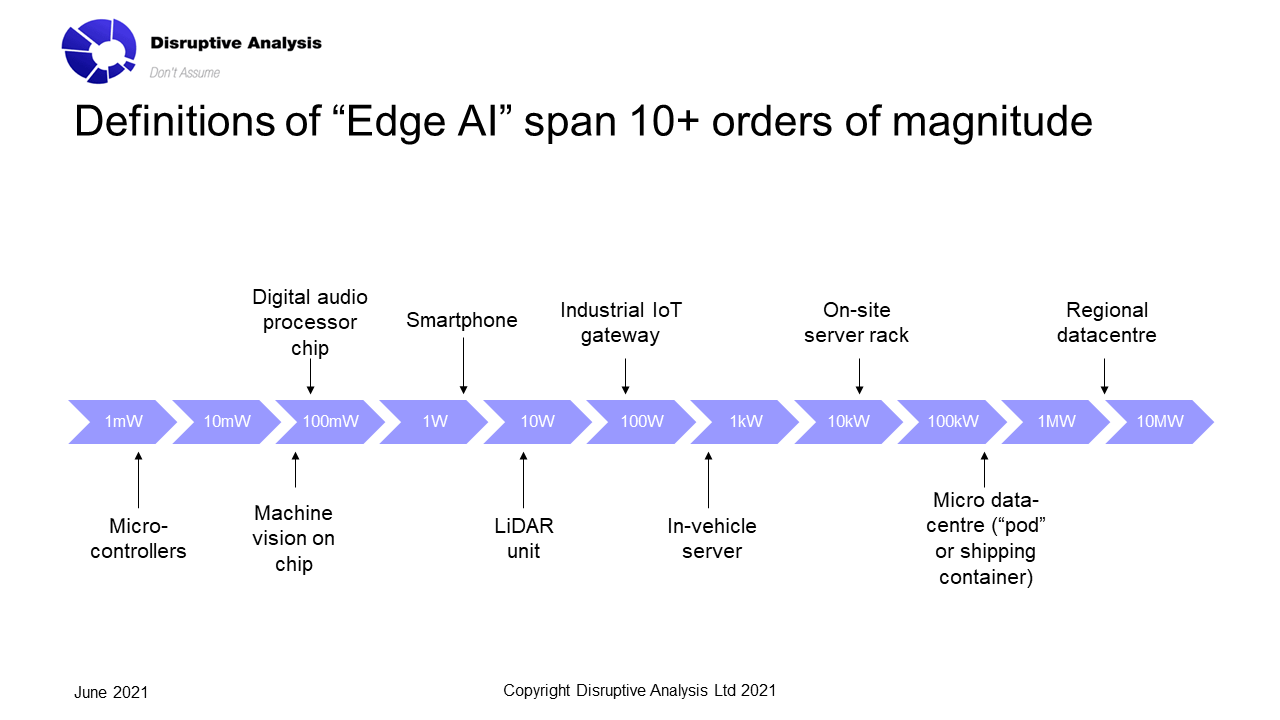

In contrast, telcos' customer-facing cloud, edge and data offers have been much slower to emerge. The focus and hype about MEC has meant operators’ emphasis has been on deploying “mini data centres” deep in their networks—at cell towers or aggregation sites, or fixed-operators’ existing central office locations. Discussion has centred on “low latency” applications as the key differentiator for CSP-enabled 5G edge. The focus has also been centred on compute rather than data storage and analysis. Few telcos have given much consideration to "data at rest" rather than "data in motion" - but both are important for developers.

This has meant a disconnect between the original MEC concept and the real needs of enterprises and developers. In reality, enterprises need their data and compute to occur in multiple locations, and to be used across multiple time frames—from real time closed-loop actions, to analysis of long-term archived data. It may also span multiple clouds—as well as on-premise and on-device capabilities beyond the network itself.

What is needed is a more holistic sense of “networked cloud” to tie these diverse data storage and processing needs together, along with documentation of connectivity and the physical source and path of data transmission.

Potentially there are some real sources of telco differentiation here - as opposed to some of the more fanciful MEC visions, which are more realistically MNOs just acting as channel partners for AWS Outposts and Azure's equivalent Private MEC.

An example of the “networked cloud”

Consider an example: video cameras for a smart city. There are numerous applications, ranging from public transit and congestion control, to security and law enforcement, identification of free parking spots, road toll enforcement, or analysing footfall trends for retailers and urban planners. In some places, cameras have been used to monitor social-distancing or mask-wearing during the pandemic. The applications vary widely in terms of immediacy, privacy issues, use of historical data, or the need for correlation between multiple cameras.

CSPs have numerous potential roles here, both for underlying connectivity and the higher-value services and applications.

But there may be a large gap between when “compute” occurs, compared to when data is collected and how it is stored. Short-term image data storage and real-time analysis might be performed on the cameras themselves, an in-network MEC node, or at a large data centre, perhaps with external AI resources or combined with other data sets. Longer-term data for trend analysis or historic access to event footage could be archived either in a city-specific facility or in hyperscale sites.

(I wrote a long article about Edge AI and analytics last year - see here)

For some applications, there will need to be strong proofs of security and data custody, especially if there are evidentiary requirements for law enforcement. That may extend to knowing (and controlling) the specific paths across which data transits, how it is stored, and the privacy and tamper-resistance compliance mechanisms employed.

Similar situations—with both opportunities and challenges—exist in verticals from vehicle-to-everything to healthcare to education to financial services and manufacturing. CSPs could become involved in the “networked cloud” and data-management across these areas—but they need to look beyond narrow views of edge-compute. Telcos are far from being the only contenders to run these types of services, but some operators are taking it seriously - Singtel offers video analytics for retail stores, for instance.

Location-specific data

As a result, the next couple of years may see something of a shift in telcos’ discussions and ambitions around enterprise data. There will be huge opportunities emerging around enterprise data’s chain-of-custody and audit trails—not only defining where processing takes place, but also where and how data is stored, when it is transmitted, and the paths it takes across the network(s) and cloud(s).

(A theme for another newsletter article or LI post is on enterprises' growing compliance headaches for data transit - especially for international networks. There may be cybersecurity risks or sanctions restrictions on transit through some countries or intermediary networks, for instance. Some corporations are even getting direct access into Internet exchanges and peering-points for greater control).

In some cases, CSPs will take a lead role here, especially where they own and control the endpoints and applications involved. Then they can better coordinate the compute and data-storage resources. In other cases, they will play supporting roles to others that have true end-to-end visibility. There will need to be bi-directional APIs—essentially, telcos become both importers and exporters of data and connectivity. This is especially true in the mobile and 5G domain, where there will inevitably be connectivity “borders” that data will need to transit. (A recent post on the need for telcos to take on both lead and support roles is here)

There may be particular advantages for location-specific data collected or managed by operators. For example, weather sensors co-located with mobile towers could provide useful situational awareness both for the telco’s own operational purposes as well as to enterprise or public-sector customers, such as smart city authorities or agricultural groups.

Telcos also have a variety of end-device fleets that they directly own, or could offer as a managed service—for instance their own vehicles, or city-wide security cameras. These can leverage the operator’s own connectivity (typically 5G) as well as anchor some of the data origination and consumption.

Conclusion

Telecom operators should shift their enterprise focus from mobile edge computing (MEC) to a wider approach built around "networked data". Much of the enterprise edge will reside beyond the network and telco control, in devices or on-premise gateways and servers. Essentially no enterprise IT/IoT systems will be wholly run "in" the 5G or fixed telco network, as virtual functions in a 3GPP or ORAN stack.

They instead should look for involvement in end-point devices, where data is generated, where and when it is stored and processed—and also the paths through the network it takes. This would align their propositions with connectivity (between objects or applications) as well as property (the physical location of edge data centres or network assets).

There are multiple stages to get to this new proposition of “networked cloud”, and not all operators will be willing or able to fulfil the whole vision. They will likely need to partner with the cloud players, as well as think carefully about treatment of network and regulatory boundaries.

Nevertheless, the broadening of scope from “edge compute” to “networked cloud” seems inevitable. The role of telcos as pure-play "edge" specialists makes little sense and may even be a distraction from the real opportunities emerging at higher levels of abstraction.

The original version of this article is at https://blog.cloudera.com/telco-5g-returns-will-come-from-enterprise-data-solutions/

I'll be speaking on an upcoming webinar with @cloudera about "Enterprise data in the #5G era" on May 4, 2022 - https://register.gotowebinar.com/register/3531625172953644816

#cloud #edgecomputing #5G #telecoms #latency #IoT #smartcities #mobile #telcos

It's under scrutiny as part of the US Congress House Judiciary Committee report on antitrust

Other governments also focus on "platforms", especially Amazon, Facebook, Google, Apple and a few others.

Typically, traditional telcos cheer on these moves against companies they (still!) wrongly refer to as "OTTs".

Yet there's a paradox here. While there are indeed concerns about big-tech monopoly abuse that must be addressed by regulators... they're not the only platforms that could be captured by the law.

I've lost count of the times I've heard "the network as a platform", or 5G is a platform" with QoS, network slicing etc often hyped as the basis for the future economy.

Yet telcos can have as much lock-in as Apple or Amazon. I can't get an EE phone service on my Vodafone mobile connection. I can't port-out my call detail records & online behaviour to a new operator. There's no "smart home portability law" if I sign up to my broadband provider's service. Or slice portability laws for enterprises.