Two very important trends are occurring in tech I'm following at the moment, so I thought it might be fun to combine them:

- The emergence of #GenerativeAI, for answering questions, generating images and sounds, and potentially a whole lot more. OpenAI #ChatGPT

is the current best-known, but there are dozens of others using

language models, transformers & other techniques. Some people are

suggesting it will redefine web search - and potentially an awful lot

more than that. Some even see it as a pivotal shift in technology,

society and "skilled" employment.

- The re-emergence of discussions around #NetNeutrality and associated regulation relating to technology platforms, telcos and networks, like the ridiculous (un)#fairshare & #InternetTrafficTax concept being pitched in Europe by lobbyists. In the UK, Ofcom

recently concluded a consultation on whether changes to NN rules should

be made (I sent in a reply myself - I'll discuss it another time).

So, I asked ChatGPT what it thought about NN, over a series of

questions. I specifically focused on whether it helps or hinders

innovation.

The transcript is below, but some thoughts from me first:

- The text is good. Almost alarmingly good. I found myself

saying "good point" a few times. This is probably because it gives

reasons in fairly long lists, not just "3 bulletpoints for a slide".

- It seems pretty even-handed, with "proponents say this, others say that"

- You

can sense that its training base tends to give it "common" responses

and frequently-cited arguments. That doesn't mean they're wrong, but it

can lack nuance, or repeat some common *fallacies* as well.

- The long-list approach and comments is quite good at highlighting the need for multiple approaches

& reconciling them. A single statistical approach isn't enough -

there are also qualitative questions to ask, surveys to undertake and

multiple angles to absorb. ChatGPT understands the issue is complex,

even if it cannot resolve the complexity itself. Simple answers are

wrong.

- I was particularly impressed with the response to my question on cross-border effects, and to separating NN vs. funding effects.

- It

struggled with the last question, about Internet and non-Internet

innovation. EDIT: I just realised that it ignored my typo, and

understood that I meant "directly" when I wrote "direct" in my question

- I'd

be very worried if I did bog-standard "content generation" for

clickbait blogs, "bucketshop" market research, or corporate social

posts. This is all perfectly-usable general blurb if you need slabs of

text nobody is going to really delve into too deeply.

All that said, I don't think this is (yet) a gamechanger in terms of

analysis and argument. It's good for collating a lot of "food for

thought", but as others have pointed out, it can also be "confidently

wrong", sometimes in amusing ways.

In a separate chat, I asked it for a contrarian's view of #5G use-cases. While it was right on some things ("Some argue that the vast majority of #IoT devices do not require the high speed and low latency that 5G provides and that the hype around IoT is overblown.") others were less convincing: ("Some

argue that 5G may not provide the low latency and high reliability that

is being promised, and that there are other technologies, such as wired

connections, that are better suited for applications such as autonomous

vehicles"). If there's one thing less relevant to self-driving cars than 5G, it's fixed broadband!

Anyway - enjoy the debate treanscribed in full, below.

(Note: the image for this article came from Stable

Diffusion, when I asked for a picture showing "An advanced AI debating

Net Neutrality")

Me: Does net neutrality help innovation?

ChatGPT: Net neutrality has been a topic of much

debate, with proponents arguing that it promotes innovation and others

arguing that it stifles it.

Proponents of net neutrality argue that it helps to level the

playing field for new entrants and small businesses by preventing

Internet Service Providers (ISPs) from discriminating against certain

types of traffic or services. This, in turn, encourages innovation, as

entrepreneurs and startups are free to bring new products and services

to market without fear of being blocked or slowed down by ISPs.

On the other hand, opponents of net neutrality argue that it creates

a regulatory burden that stifles innovation and investment in the

broadband industry. They argue that without the ability to prioritize

different types of traffic, ISPs will be unable to effectively manage

their networks and may be forced to limit investment in new

infrastructure and technologies.

Ultimately, the impact of net neutrality on innovation is a complex

and highly debated issue, and there is no clear consensus on whether it

helps or hurts innovation. However, proponents of net neutrality

generally believe that it promotes a free and open internet that

supports innovation and competition, while opponents believe that it

imposes unnecessary regulation that stifles growth and investment.

Me: What research is necessary to reach a better conclusion?

ChatGPT: To reach a more definitive conclusion on

the impact of net neutrality on innovation, several types of research

would be necessary, including:

- Economic studies: Economic studies could analyze the impact

of net neutrality regulations on investment and innovation in the

broadband industry, as well as the impact on consumer prices and access

to broadband services.

- Case studies: Case studies of countries

or regions with and without net neutrality regulations could provide

valuable insights into the real-world effects of these regulations on

innovation and investment in the broadband industry.

- Surveys and

interviews: Surveys and interviews with entrepreneurs, startups, and

industry experts could provide insights into the impact of net

neutrality on the ability of new entrants to bring new products and

services to market.

- Technical studies: Technical studies could

examine the impact of net neutrality regulations on network management

and traffic prioritization, and assess the potential impact on network

performance, reliability, and security.

- Long-term data analysis:

Long-term data analysis could track changes in investment, innovation,

and consumer prices over time in regions with and without net neutrality

regulations, providing valuable insights into the long-term impact of

these regulations.

Overall, a comprehensive and multi-disciplinary approach to

research, combining economic, case study, survey, technical, and data

analysis methods, would be necessary to reach a more definitive

conclusion on the impact of net neutrality on innovation.

Me: How would you measure innovation in this context?

ChatGPT: Measuring the impact of net neutrality on

innovation is a complex task, as innovation can take many forms and can

be difficult to quantify. However, several metrics could be used to

measure innovation in this context, including:

- Investment in research and development (R&D): This could

be measured by tracking the amount of investment in R&D by

broadband companies and startups, as well as the number of patents filed

in relevant areas.

- New product and service launches: This could

be measured by tracking the number of new products and services

introduced by broadband companies and startups, as well as the market

adoption and success of these offerings.

- Entrepreneurial

activity: This could be measured by tracking the number of new startups

founded in the broadband industry, as well as the success of these

startups in attracting investment and bringing new products and services

to market.

- Consumer benefits: This could be measured by

tracking changes in consumer prices, access to broadband services, and

the availability of new and innovative online services and applications.

- Network

performance and reliability: This could be measured by tracking changes

in network speed, latency, and uptime, as well as the ability of

networks to handle new and innovative applications and services.

While these metrics are not exhaustive, they provide a good starting

point for measuring the impact of net neutrality on innovation in the

broadband industry. By tracking changes in these metrics over time in

regions with and without net neutrality regulations, researchers could

gain valuable insights into the impact of these regulations on

innovation.

Me: A lot of those metrics are international. More regions

with net neutrality might increase innovation globally, not locally. How

do you account for that?

ChatGPT: You are correct, some of the metrics

mentioned could be influenced by factors beyond the borders of a single

region. To account for this, it would be important to consider both the

local and global impact of net neutrality on innovation.

For example, to measure the local impact of net neutrality,

researchers could compare the metrics mentioned in regions with and

without net neutrality regulations, taking into account factors such as

the local economy, cultural and regulatory environment, and the state of

the broadband industry in each region. This would provide valuable

insights into the specific impact of net neutrality on innovation within

those regions.

To measure the global impact of net neutrality, researchers could

compare these metrics on a global scale, taking into account factors

such as the state of the global economy, the state of the broadband

industry globally, and the regulatory environment in different regions.

This would provide a broader perspective on the impact of net neutrality

on innovation globally, and could help to identify any trends or

patterns that may not be apparent from a regional analysis alone.

Overall, it is important to consider both the local and global

impact of net neutrality on innovation to gain a complete and accurate

understanding of the impact of these regulations on the broadband

industry and innovation more broadly.

Me: How would we know if net neutrality had a larger effect on innovation than availability of financing for startups?

ChatGPT: Determining the relative impact of net

neutrality versus the availability of financing on innovation can be

challenging, as these factors are often interrelated and can have

complex and interconnected effects. However, several approaches could be

used to isolate the impact of each factor, including:

- Comparative studies: Researchers could compare regions with

and without net neutrality regulations, but with similar levels of

financing available for startups. By controlling for the availability of

financing, researchers could isolate the impact of net neutrality on

innovation.

- Historical analysis: Researchers could analyze data

from periods of time when net neutrality regulations were in place or

not in place, and compare this data with changes in the availability of

financing for startups. This would help to identify any correlations

between net neutrality and innovation, independent of changes in

financing.

- Causal inference methods: Researchers could use

causal inference methods, such as regression analysis, to model the

relationship between net neutrality, financing, and innovation, while

controlling for other factors that could influence these relationships.

- Survey

and interview-based research: Researchers could survey and interview

startups, entrepreneurs, and industry experts to gain insights into the

relative importance of net neutrality and financing for innovation. This

would provide valuable qualitative data to complement the quantitative

data obtained from other research methods.

Overall, a multi-disciplinary and multi-method approach,

incorporating comparative studies, historical analysis, causal inference

methods, and survey and interview-based research, would be necessary to

determine the relative impact of net neutrality and financing on

innovation in a robust and comprehensive manner.

Me: How do you distinguish innovations that direct relate to

Internet access, compared to those which involve non-Internet

applications and technologies?

ChatGPT: Distinguishing innovations that directly

relate to Internet access versus those that involve non-Internet

applications and technologies can be challenging, as many innovations

are influenced by both Internet access and non-Internet technologies.

However, several approaches could be used to differentiate these types

of innovations, including:

- Technical classification: Innovations could be classified

based on their underlying technologies, with innovations that rely

primarily on Internet access being classified as Internet-related

innovations and innovations that rely primarily on non-Internet

technologies being classified as non-Internet-related innovations.

- Market

classification: Innovations could be classified based on the markets

they serve, with innovations that serve primarily Internet-based

markets, such as online commerce or online communication, being

classified as Internet-related innovations and innovations that serve

primarily non-Internet-based markets, such as manufacturing or

agriculture, being classified as non-Internet-related innovations.

- End-user

classification: Innovations could be classified based on their

end-users, with innovations that are primarily designed for use by

individuals accessing the Internet being classified as Internet-related

innovations and innovations that are primarily designed for use by

individuals not accessing the Internet being classified as

non-Internet-related innovations.

It is important to note that these classifications are not mutually

exclusive, and that many innovations may have elements of both

Internet-related and non-Internet-related technologies, markets, and

end-users. Nevertheless, using these classifications can provide

valuable insights into the extent to which innovations are influenced by

Internet access, and can help to distinguish Internet-related

innovations from non-Internet-related innovations.

- Collect more granular data, or make reasoned estimates, of breakdowns of data traffic in your country & trends over time. As well as #FWA vs #MBB & indoor vs outdoor, there should be a split between rural / urban / dense & ideally between macro #RAN vs outdoor #smallcell vs dedicated indoor system. Break out rail / road transport usage.

- Develop a specific policy (or at least gather data and policy drivers) for FWA & indoor #wireless. That feeds through to many areas including spectrum, competition, consumer protection, #wholesale, rights-of-way / access, #cybersecurity, inclusion, industrial policy, R&D, testbeds and trials etc. Don't treat #mobile as mostly about outdoor or in-vehicle connectivity.

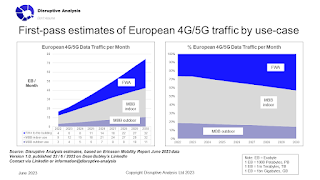

- View demand forecasts of mobile #datatraffic and implied costs for MNO investment / capacity-upgrade through the lens of detailed stats, not headline aggregates. FWA is "discretionary"; operators know it creates 10-20x more traffic per user. In areas with poor fixed #broadband (typically rural) that's potentially good news - but those areas may have spare mobile capacity rather than needing upgrades. Remember 4G-to-5G upgrade CAPEX is needed irrespective of traffic levels. FWA in urban areas likely competes with fibre and is a commercial choice, so complaints about traffic growth are self-serving.

- Indoor & FWA wireless can be more "tech neutral" & "business model neutral" than outdoor mobile access. #WiFi, #satellite and other technologies play more important roles - and may be lower-energy too. Shared / #neutralhost infrastructure is very relevant.

- Think through the impact of detailed data on #spectrum requirements and bands. In particular, the FWA/MBB & indoor splits are yet more evidence that the need for #6GHz for #5G has been hugely overstated. In particular, because FWA is "deterministic" (ie it doesn't move around or cluster in crowds) it's much more tolerant of using different bands - or unlicensed spectrum. Meanwhile indoor MBB can be delivered with low-band macro 5G, dedicated in-building systems (perhaps mmWave), or offloaded to WiFi. Using midband 5G and MIMO to "blast through walls" is not ideal use of either spectrum or energy.

- View 5G traffic data/forecasts used in so-called #fairshare or #costrecovery debates with skepticism. Check if discretionary FWA is inflating the figures. Question any GDP impact claims. Consider how much RAN investment is actually serving indoor users, maybe inefficiently. And be aware that home FWA traffic skews towards TVs and VoD #streaming (Netflix, Prime etc) rather than smartphone- or upload-centric social #video like TikTok & FB/IG.

Telecoms regulation needs good input data, not convenient or dramatic headline stats.